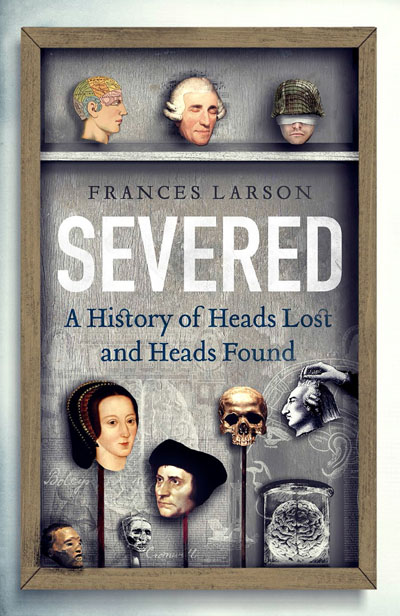

Severed – A history of heads lost and heads found

By Frances Larson

Author’s Homepage: http://franceslarson.com

Author’s Twitter: https://twitter.com/FrancesRLarson

At the risk of appearing macabre, I’ll admit that heads have been on my mind lately.

Utterly mesmerised by Hannah Kent’s fiction-inspired-by-fact Burial Rites, I fought back tears and nausea as I read of the final moments before murderess Agnes is lead to the axe-wielding executioner. The method of her fate is cruelly rehearsed immediately prior to her death, with her co-convicted sent out first.

“Tóti,” she said in a panicked voice.” Tóti, I don’t think I’m ready. I don’t think I can do it. Can you make them wait? They have to wait.”

Tóti pulled Agnes closer to him and squeezed her hand.

“I won’t let go of you. God is all around us Agnes. I won’t ever let go.”

The woman looked up into the blank sky. The sudden sound of the first axe fall echoed through the valley.

I peeked through fingers spread across my face as Ragnar Lothbrok and pals struck heads off foe (and sometimes friend) in television’s Vikings Season 1 and Season 2. The trailer for coming-soon Vikings Season 3 depicts Ragnar on his long boat, with enemy heads strung up across the cross beam. The victorious warrior is grinning; those other miserable faces are not.

As I write this review in January 2015, the world is reeling from news that yet another ISIL hostage has been murdered by beheading. Consistent with other executions that preceded it, the captor applied a small weapon, by hand.

The brutality of the act that removes a human head from its body seems so destructive, so shocking and so inherently unnatural that most of us recoil at the idea. The very concept seems inhuman.

Or is it?

In Severed – A history of heads lost and heads found, Frances Larson presents a detailed and well-researched scientific, psychological and social history. In it, she essentially argues that we’re kidding ourselves if we think that head removal and objectification is only something that criminals and savages do.

With a focus on European and American white histories – the ‘civilised West’ in her own words – Larson investigates the obsession of peoples with severed heads and skulls. Starting with Oliver Cromwell’s cranium, she explores heads that are irresistible, shrunken, trophy, deposed, framed, potent, bone, dissected and living. According to Larson, “Peoples’ heads have been, and in some cases continue to be, displayed in the name of science, warfare, religion, art, justice and politics.” Her chapters are “as much about decapitation as they are about the cultural power of the severed head in our society.” Following are a few examples.

The West’s obsession with crania is clear in the world’s many museums, which keep huge collections of heads and skulls, usually donated or acquired from private collectors over the past 200 years. While some of these heads were originally sourced during above-board anthropological studies, many were generated illegally via grave-robbing and unethical behaviour during colonial and war times. Respectable white men – yes, usually men – would source recently-killed bodies or dig up rotting corpses, remove the heads, and boil them down to generate skulls. These men often had families, attended church, were respected and admired. Their curiosities about culture, race, intelligence and indeed morality drove them to behave in a way that most of us now judge as barbaric.

As explored recently by Richard Flanagan in his award-winning novel The Long Road to the Deep North, for many people World War II is linked inextricably with the brutality of the Japanese soldiers in the jungles of the Asia Pacific. What’s reported less often is that Allied soldiers were also practicing the removal of enemy heads and body-parts. Larson says, “One forensic report estimated that the heads were missing from 60% of the Japanese dead repatriated from the Mariana Islands in 1984.” Trophy taking was apparently common practice. “Most soldiers knew it happened and accepted is as inevitable under the circumstances: after a few weeks on duty, they had seen far worse,” writes Larson.

Larson presents the interesting tale of shrunken heads from South America to highlight how cultural perspectives shape what is perceived as normal and what is not. Dating back to at least the 16th century, the Shuar people (around the region of Ecuador/Peru) created shrunken human heads as part of complex rituals designed to harnessed the power of the soul after death. The taking of the heads occurred in organised raids, and was a socially-accepted form of violence. With the arrival of Europeans and Americans, by the late 19th century head-hunting was a booming international trade, with heads sent home and appearing in shops, auction houses, museums and private homes. Larson says, “The shrunken heads in our museums are not the remnants of some untouched, savage way of life as much as they are the product of the economics of colonial expansion and the power of a fantasy about ‘savage culture’”.

All in all, it’s a fascinating book. The explorations and descriptions of the guillotine are particularly gory – I shall spare the reader excerpts – but still utterly compelling reading. Surprisingly, it was only in 1939 that the use of the guillotine was banned in France, after the execution of German criminal Eugen Weidman in broad daylight and in front of a larger-than-expected crowd. According to Larson, the ban occurred “not because [executions] were too horrifying to watch, but because the authorities knew that people will watch them no matter how horrifying they are.”

Larson’s research and reporting of the role of heads and skulls in art, science and medicine is excellent. As an example:

“Dissection is about priorities: some parts are cut away so that other parts can be seen more clearly. Skulls are sawn through to get to brains; brains are pulled out to yield skulls. And, in the process, a person is turned into a series of artefacts that each belong in their own category: skulls, brains, hemiheads, pineal glands, optic nerves. Each category of thing has its own value to society, a value which rises and falls with the intellectual tide, the technological facilities of the time, and the broader cultural milieu. The rise of the brain has as much to do with the history of chemistry and preservatives as with the theories of the scientists involved.”

Although Larson is explicit in her decision to focus her writing on the intersection of modern white history with heads and beheading, a venture into other cultures would also be fascinating. I found myself wondering about the Viking, Japanese, Incan, Greek, Roman and Islamic perspectives often whilst reading. But a book can only be so long.

If your heart is brave and your stomach strong, if you are interested in science and how it interacts with culture, history and people past and present, this book is a must-read.

—

Sarah is a freelance science writer based in Adelaide, South Australia. She established her writing business in early 2012 after 15 years working in immunology research and science communication in Australia and Indonesia. She currently works with a range of clients in science, medicine, research, education, outreach and communications. She has a Bachelor of Medical Science with honours, a PhD and a Graduate Diploma in Sciences Communication. When not reading and writing, Sarah indulges in cooking, eating and exercise.

Sarah’s Blog Homepage: http://sciencesarah.wordpress.com

Sarah’s Science for Life 365: http://scienceforlife365.wordpress.com

Sarah’s Twitter: https://twitter.com/sciencesarah

Reblogged this on Literally Science and commented:

Australian Science Journalist, Sarah Keenihan, reviews Severed: A history of heads lost and heads found. Check it out 🙂